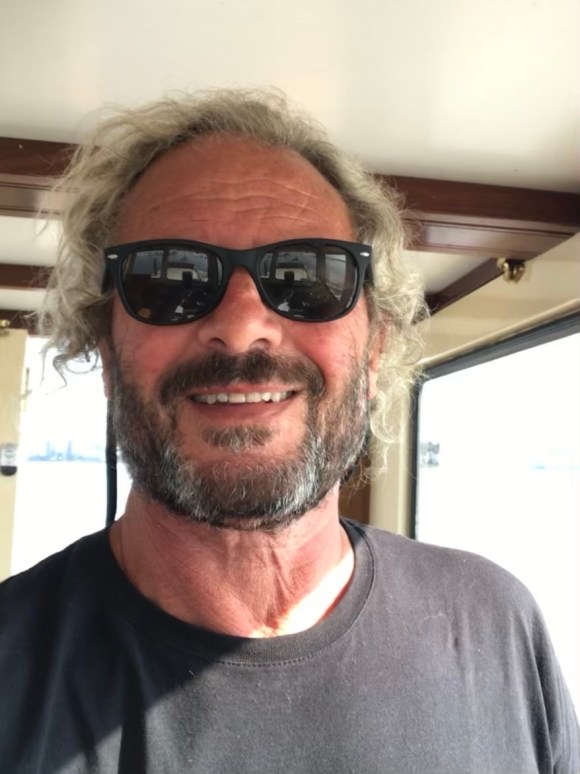

Nomad Si – by name and nature.

In truth I’m a bit of an old hippy, nomad and pirate. For this my parents and general ancestry are to blame. On my mum’s side I’m from a long line of farmers from SE England – my grandfather had a market garden on what is now part of Heathrow airport – and on my father’s I’m a third generation Eastern European Jew-ish (geddit?) refugee. This peculiar ethnic mix makes me a typical Londoner – for which I give thanks. Rumour has it that my great-grandparents Alexei and Sarah Chapkofsky walked across Russia with my grandfather Louis (sometimes Lawrence) – later Lou Lawson – as a babe in arms. When they eventually reached some port or other, they probably thought they were buying a ticket to America, not London’s East End – didn’t they all?

Today, so called “mixed” marriages, religious or ethnic, are so commonplace, and unremarkable, that the average London school playground resembles the living embodiment of Blue Mink’s beautiful dream – Melting Pot or Desmond Tutu’s Rainbow Nation, but when my parents met in the early 1950’s it wasn’t at all like that. The “…Rabbis and the friars..” still cared what religion you chose. Not that either of their families was very religious, but just after the second world war it was still not really “done” to marry “out”.

Rabbis and the friars – Vishnus and the gurus – We got the Beatles or the Sun God – Well it really doesn’t matter what religion you choose…

My mother told a story about the first time she’d taken my dad to meet her family, at Wellcross Farm in West Sussex. Afterwards my Granny remarked that: “..he seems quite normal.” – my dad being the first Jew she had ever met – to which my mother allegedly snapped back: “What did you expect, a tail?”. There was some attempt to stop them marrying – on the basis that it would never work. When my dad was called back into the army for a few months they tried to separate, and my Grandfather – Fred Miller – took my mum to Paris to get over my dad. However, love won out and they married in 1952. My father became firm friends with my mum’s two older brothers, Jack and Arthur. And he always said that Fred, who died while mum was pregnant with me, was very fond of him and that he used to sneak him off for a sherry or two before dinner, away from Granny’s disapproving gaze. She was the youngest of ten and had a very Victorian upbringing – her family always thought that she had married beneath her.

Dad’s family were another story altogether. Dominated by my matriarchal Grandma, Kitty or Kate Lawson (née Mendelsohn), they were a family of 19th century Jewish refugees, already embarked on the North West Passage out of London’s East End. That is to say, Grandma and Grandpa had made it to a mansion flat on the Edgware Road in Maida Vale, and their eldest daughter Connie to a large semi-detached on the Finchley Road in Golders Green. Doris, my Dad’s elder sister, her husband Sid Viner, their boys Brian and Larry and my mum and dad were living in two flats above a draper’s shop, on Kilburn High Road – run by Sid and dad. That is where I lived for the first eighteen months of my life, before we too made it further along the passage, in our case to Hampstead Garden Suburb (thanks to my mum’s inheritance of her ‘girl’s’ share of the farm) and the Viners to Golders Green Road. But I digress and there’ll be more about these characters later. I don’t recall ever hearing that anybody, in dad’s family, tried to put up barriers to their marriage, which could be thought of as strange, because many Jewish families would do anything to stop their sons marrying out. It was more acceptable for daughters, because then, at least under Jewish law, the children would still be Jewish, whereas us children of shiksa (non-Jewish) mothers are not – as I have been reminded, with prejudice, throughout my life – but never by any of my relatives. I think this mixed marriage was accepted by our family for several reasons. Firstly, my dad was Kitty’s only son and youngest child, spoilt rotten and could do no wrong in her eyes. If she said it was ok no-one else was going to argue. Secondly, my family, although extremely Jewish, was not in the slightest bit religious – other than a social adherence to Bar Mitzvahs, synagogue weddings and funerals. And thirdly everybody loved my mum, even if Grandma did call her a “wicked shiksa” whenever mum stood up to her, which is something very few other people ever dared to do. I think it helped that she was a nurse, and could thus be called upon to minister to her new Jewish hypochondriac family. Fortunately, Kate also took it upon herself to teach my mum to cook, otherwise I would have been brought up on overdone meat and boiled cabbage seasoned with bicarbonate of soda, and not gefilte fish, chicken soup and smoked salmon beigels.

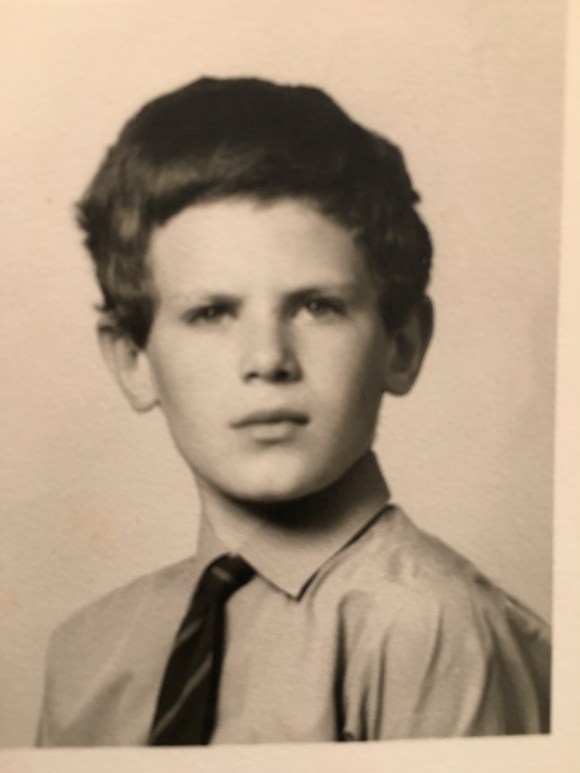

Jew-ish Boy

This mixed background makes me part of a non-visible ethnic minority that I choose to call Jew-ish. I have always felt a bit of an outsider as though, some how, I don’t really belong – I’m neither a Christian or a Jew – however, here I must quote my Grandma Kate: “Just remember my darling..” she used to say, “..by Hitler you are Jewish.” True enough, but unfortunately when I quoted this to a proselytising Lubavitcher, by the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, who was asking if I was Jewish, he didn’t get it and just carried on saying: “It doesn’t matter – G-d – has sent you here for a reason, you can convert.” The fact is, I have been subjected to mild prejudice from Jews and Christians alike throughout my life. I nearly wrote non-Jews there, but actually I don’t recall any real religious abuse from people of any other religion, in a life time of world travel, including long stints in predominantly Moslem countries. I’m not for a minute saying that I have been racially abused, in as an overt and open manner, or suffered the same level of racial hatred, as black, brown and other visible ethnic minorities, but prejudice it was all the same. Back in the 1950s and 60s anti-semitism was everyday, accepted and largely unremarkable. For example, in any school playground – but particularly in “Public” schools – if you wanted to tell another kid not to be “tight” or mean, people would say “Don’t be such a Jew.” or “Don’t be a Yid.” Even my non Jewish cousins would say it, may be not to my face, but about another kid at school and likely unaware that I would think anything of it. Like I say, it was unremarkable, it was established. I faced a more serious example of how anti-semitism was institutionalised when it came to my parents’ choice of school for me.

My father Derek, had been a scholarship boy, the first in his family to go to grammar school, he attended Reines, which was local to them in Stepney. He always said that both Connie and Doris could have gone there, were it not for the fact that they were girls and obliged by my Grandma to leave school and start working in the family businesses – black marketeering, fencing (stolen goods), book-making, fish and chips – as soon as they could leave school at fourteen. He did well at school, and had his conscription deferred until he left at eighteen. Then – in 1946 – he was called up. He was bright and selected for officer training at Aldershot – quite something for a Jewish boy from Stepney in London’s East End. He never talked much about it, but I know he suffered a lot of anti-semitic abuse, from the more typical English officer class, and at least once defended his honour in the boxing ring. This will astonish any one who knew my dad, as he had a horror of violence, and was a self-professed devout coward – having watched my Grandma beat up my Grandpa throughout his childhood, not to mention any teacher that had the temerity to criticise her Derek. To add insult to injury, as a newly qualified Second Lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps, he was posted to Hamburg in Germany, and tasked with organising the transport of troops to prevent the mass exodus of concentration camp survivors to Palestine through Hamburg’s docks. This apparently involved turning water-cannon on his skeletal Jewish brethren. He survived, partly aided by his kind and compassionate commanding officer – Colonel O’Flaherty, who became a lifelong friend (curiously they ended up retiring to the same village). But what has this got to do with his choice of school for me, I hear you ask? These formative experiences, meant that by the time I was born and we were living in Hampstead Garden Suburb, my dad had lost his cockney accent, spoke “RP” English and had become to all intents and purposes “middle class” with the aspirations to match, these included thinking a private education would give his children the best possible start in life. He put my name down for Highgate School – the school that sits atop Highgate Hill, founded under royal charter of Elizabeth I, by Sir Roger Cholmeley in 1565.

My father would have liked to send me to a boarding school, but my mother – who had been sent away to school aged seven, and harboured bitter memories of cruelty and privation – refused. “I told him: over my dead body!” she said in explanation to me later. So a lesser fate awaited me as a day boy. But something curious was going on, and it would be many years before I learnt the scandalous truth. Come school age, when the two elder Savage boys (our next door neighbours) were already at Highgate in the “Prep.” school, I was sent first to Henrietta Barnett Infant School and then to Hampstead Garden Suburb Junior School – the local state schools. Why not Highgate? For years I was told that it was because my name had gone down late, that for the most popular public schools you had to have your name down before you were born! The truth was far more sinister. Highgate – and no doubt other public schools at the time, in the 1960s – operated a Jewish quota. It was not until I was ten at the end of year five, that I finally went to Highgate, and even then into a class of boys who were mostly a year younger than me – their schooling having been obviously so much better than at my state school. Presumably, Highgate considered a Jewish quota necessary to prevent their predominately white Christian intake from being overshadowed by cleverer rich Jews, of whom there were many in the North London catchment area of the school. Trope or not, certainly in my recall the top of the “A” stream was always dominated by the Cohens, Oppenheims and Rothschilds. They had reason to be afraid of us. There were, not surprisingly, even fewer boys of colour. If there was a quota I don’t know, but I recall only one or two Black kids, a few Arabs and a couple of Sikhs. Writing this now it’s really hard to believe that this was legal in the 1960’s and it’s something that’s shocking to my children. It didn’t end there. In the “juniors” we had the normal daily assembly that included Christian prayers and hymns etc. just as in every other school in the country, with occasional trips up the hill to the Elizabethan chapel in the senior school. Being a Jew-ish agnostic wasn’t really an issue then. But when I went up to senior school aged thirteen all that changed. In my induction interview, with my new House Master, I was asked what religion I was. “None” I answered. This was not acceptable. “It says here that you are Jewish, boy!” the teacher told me (why did he ask me then?). “Well.” I said, “My father was Jewish, and my mother was Christian, but our family is not religious.” “You have to have a religion.” he insisted, “Do you want to go to chapel or Jewish circle, you choose?” “OK – well I choose both then.” I said, “I’ll go to chapel with the other boys, most of the week, but to Jewish circle on Thursdays when the Christian boys go to St. Michael’s church for the weekly service there.” This seemed to satisfy him. And that’s what I did, until I discovered that the visiting Rabbi didn’t really want me in his Jewish circle at all.

For some weeks after, when most of the other lads filed off through Highgate village to St Michaels, I joined the Jewish boys in Jewish circle, which took place in one of the larger classrooms, presided over by a local Rabbi. Mostly, I’d sit at the back not paying much attention. Unlike the other boys I had not had a Bar Mitzvah, so I didn’t know Hebrew and couldn’t join in with the prayers anyway. Then one day, I caught the words: “mixed marriage” from the sermonising Rabbi and started to listen. He was stridently lecturing us about the dangers of marrying out. “Think of the children of such mixed marriages,” he was saying, “they wouldn’t be Jewish, they’d be a disaster!” A disaster! That was me he was describing and calling a disaster. That was it, the last time I went to Jewish Circle. From then on I ambled off to St Michaels with my other mates on Thursdays, which had the added attraction that sometimes we could sneak off over the wall into the old overgrown part of Highgate cemetery for a quick fag on our way back to school.

The best of both worlds.

I was blissfully unaware of the dilemmas of difference through my early childhood. It seemed completely normal to me that we spent every other weekend at “the farm”, visiting Granny, Uncle Arthur, Uncle Jack and Monica and of course their three kids – my cousins – Jilly, Richard and Christopher. We made camps in hay stacks, fed the calves after tea, vaulting gates – trying but failing, accidentally on purpose, not to fall in cow shit. I worshipped Richard, who four years older than me was my country older brother. He took me bird-nesting, taught me how to blow robins’ eggs, catch sticklebacks, from the pond in a jam jar, and generally how to read the countryside. He was a dead shot too, and could hit a running rat on a rafter with a 22 rifle. West Sussex in those days was a rural idyll. We kids could run wild through the yards, across the fields and along the river Arun. Sadly, that Sussex is long lost to commuter sprawl and equestrian units. We almost always spent Christmas on the farm.

London was another story, but just as natural a habitat for me. My cousin Larry was my London older brother, who I also worshipped. Seven years older, Larry taught me the survival skills for city life – how to let off stink bombs on the tube, eat a week’s worth of roast meats in one lunch time at the Regents Hotel Carvary – literally all we could eat – I think seven platefuls was my record – and most importantly how to escape the clutches of an anti-Semitic yob by poking your finger in his eye. A skill that came in useful many years later when I was beaten up by Geordie youth in a “Straw Dogs” moment in Co. Durham.

Much of my London life was pretty bucolic too. Living in a large detached Lutchens’ house, in Turner Close, Hampstead Garden Suburb. The Hampstead Heath Extension, with its meadows, playing fields, conker trees, steams, ponds and woodland wilderness was my playground. The Heath was where I ran away to for the first time with my puppies – a story for another day. It was where we rode our bikes, dammed streams, with clay and stolen bricks, built tree houses – all the while, outlaws trying to avoid detection and capture by the brown uniformed London Corporation park keepers who policed the Heath, and later, from age fourteen on, the Heath was where I went alone or with other friends to smoke joints, and avoid the fuzz!

…….

To be continued

…………………….